Scott Imhoff, Ph.D., (BS physics ’82) has carved a unique career path as an Engineering Fellow at Raytheon Technologies assigned to developing the control segment for present and future GPS satellites. His work—and his extensive portfolio of contributions to the space satellite engineering science—all began with a sense of belonging at IUPUI.

Imhoff enrolled in the physics department in the School of Science, and as someone living with autism spectrum disorder 1, before this he’d often felt like he didn’t belong.

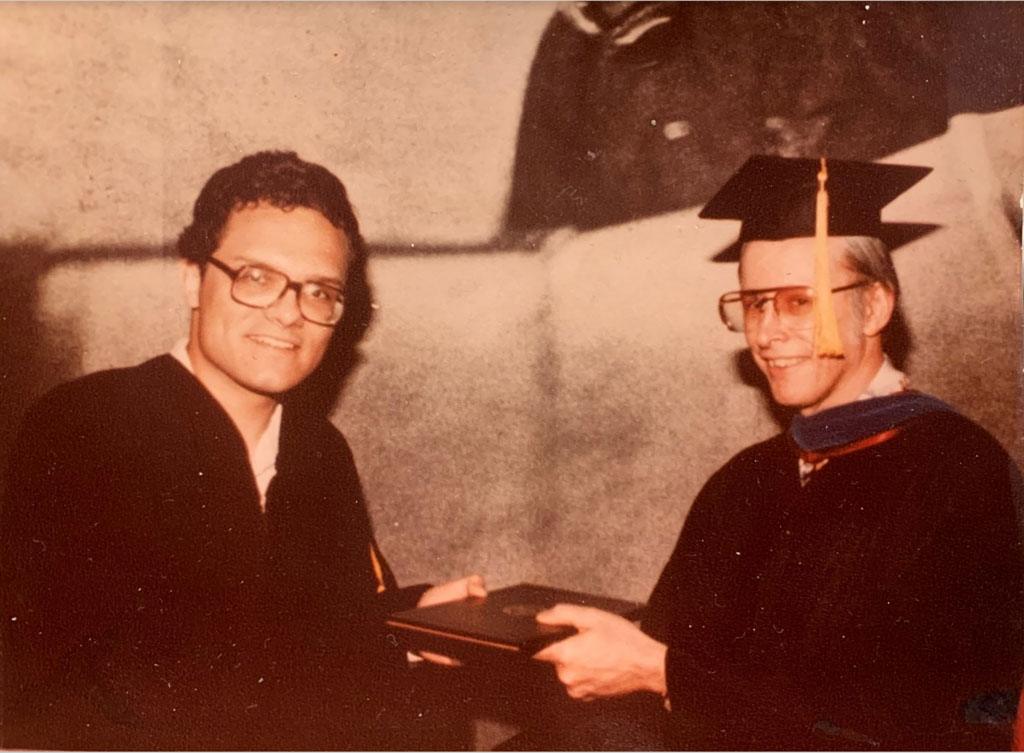

“I knew that I was not a person that would fit in easily anywhere because of the neurodiversity that I have,” said Imhoff. “But I will never forget Professor Forrest Meiere took me aside and he said, ‘You are one of us.’ My experience at the Physics Department at IUPUI was the first time that people explicitly told me I was one of them, that I belonged, and was welcome. Professors Marvin Kemple, Nageswara Rao, and Kashyap Vasavada made me feel so safe, and I made it my objective to be just like them.”

During his time at IUPUI, Imhoff was drawn to physics and the way it defines the world in which we live. He also enjoyed seeing the interplay between mathematics and the physical world. During this time, Imhoff began work that would later culminate in his co-invention of the high isolation transmit/receive switch separating transmit and receive for phased array radar, beginning his love of blending physics and mathematics in his work.

Not only did he learn the foundations of these subjects, Imhoff says he gained a new way to approach the work.

“The faculty at that time modeled for me a different kind of learning in which you know the theorem or physical law off the top of your head, rather than needing to look it up,” said Imhoff. “I remember Professor Meiere had very few books in his office because he would learn the concepts and didn’t need to reference it. They modeled an understanding where you have it at the tip of your tongue, on the ready.”

This ability to think on his feet would come in handy throughout Imhoff’s professional life. After IUPUI, Imhoff went on to earn a master’s degree in physics at Purdue in West Lafayette. He took a job at Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Electronic Systems Group, which ultimately became part of Northop Grumman. At the age of 36, Imhoff became the youngest person at that time in to earn the rank of Fellow Engineer and earn Westinghouse’s highest technical achievement award. The following year he received the division’s highest fellowship, the Advanced Study Award, which he used to complete a PhD in mathematics at University of Maryland Baltimore County. Interestingly, a Number Theory course he completed at IUPUI 15 years earlier transferred to the PhD program. He says these accomplishments tied back to learning to think on his feet.

“If there was ever a crisis, I would walk into the technical meeting, and they knew that I would have answers to turn things toward a better course,” said Imhoff. “A few years into my career, they were going to cancel a multi-million-dollar sensor project because only one element out of an array of scores of elements had been built by a certain testing milestone. I knew I could take the testing data from that one element and mathematically extrapolate the implied performance for the whole array using what I learned in an optics and wave course I had at IUPUI, complemented with some mathematics I had at both at IUPUI and Purdue.”

Imhoff considers himself a “mathematical physicist,” since his work in GPS requires equal parts math and physics. Throughout his 40-year career at Northrop Grumman, and later at Raytheon Technologies, he’s submitted over 100 inventions, starting at age 20 and continuing today. Imhoff has also seen the evolution of modern science, having collaborated with pioneers in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) relating to his work on the development of wavelets (he holds an early patent for the wavelet frame classifier).

“In the 1990s I was invited into some work with Darrell Whitley at Colorado State University. When you joined, you have this feeling that a lot had already happened in the area of AI, and you missed the start,” he said. “But looking back with hindsight, we were involved very early in that work.”

Throughout his career, Imhoff carried with him a teaching spirit that he initially fostered during a college teaching course at Purdue, where he served as a graduate teaching assistant. At Raytheon Technologies, where Imhoff has worked since 2006, one of his younger colleagues, Kendy Hall, PhD, asked Imhoff to be his mentor. Having completed a course at Denver Seminary, Imhoff saw value in “walking along side” someone as a sounding board. He went on to mentor 20 other professionals through Raytheon’s formal mentoring program. In 2018 Imhoff received Raytheon Technologies’ highest mentoring award.

“I got involved in mentoring because I was asked to be a mentor to this young PhD, who eventually did so well that he became my boss. There is no better mentoring success than to have your mentee become your boss!” said Imhoff. “As a mentor, you’re not trying to teach or train somebody, you’re just walking beside them, accompanying them and being their sounding board, sharing in their grief and joy. These relationships look a lot like chaplaincy.”

Imhoff’s instructional work continued at Buckley Air Force Base, where he helped start a master’s degree program in space operations management, and at The University of Colorado, where he co-founded their industrial doctorate program to combine science with business. The industrial PhD was created around the practical concept of providing a doctorate-level understanding of science coupled with the business knowledge of how to fund scientific work.

“The thinking was to have a combination MBA and PhD offered jointly from the department of computer science and engineering that included 600-level business school courses,” said Imhoff. “My role in this was as an expert witness of sorts to say, as someone who’s a practitioner in the industry at the PhD level, we have a need for those graduates, and these would be graduates we’d hire.”

At 62 years old, Imhoff is busier than ever, with more patents in the hopper. “The best creative work I’ve done is these past couple years, after the age of 60,” he said. Grateful for the mentors and professors who encouraged and welcomed him at an early age, Imhoff hopes that students currently studying at his alma mater understand that achievement by a certain age is a misconception.

“There is a false narrative about math and physics careers that achievement by a certain age is more important than it really is, when the opposite is true,” said Imhoff. “I finally got my PhD at age 38. It turns out, success in math and physics is about pacing yourself for a long game so you don’t burn out.”

As crucial as his mentors have been, Imhoff says among the greatest lessons he’s gained is learning oneself. He has one more piece advice for current students following in his career path of math or physics.

“Exercise discernment. The one person most qualified to judge the quality and value of your work is looking at you in the mirror,” said Imhoff. “Once you get out into the world, you may receive feedback you need to ignore. Be discerning, don’t be discouraged by guidance from people who may not know you—or your work—as well as you do. Always know that each of you is a person of great value.”